Heading into the 2025 Atlantic hurricane season, National Weather Service forecasters at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) are predicting “above-normal hurricane activity in the Atlantic basin this year.”

The season, which runs from June 1 to November 30, is estimated to dish out between 13 and 19 total named storms, with six expected to be hurricanes and three to five of those to be major (category 3 or higher) hurricanes with winds exceeding 111 mph. For the record, NOAA is more often right than wrong, with 70 percent confidence.

“NOAA and the National Weather Service are using the most advanced weather models and cutting-edge hurricane tracking systems to provide Americans with real-time storm forecasts and warnings,” the Administration’s Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick is quoted saying in a late-May press release. “With these models and forecasting tools, we have never been more prepared for hurricane season,” Lutnick posited.

In some sense, that is certainly true. These days, NOAA is equipped to provide a staggering 6.3 billion observations each day, according to WPLG (ABC Miami) hurricane specialist and storm-surge expert Michael Lowry. Despite all the technology and preparation, NOAA’s recently (and severely) shortened staff isn’t exactly running at full bore, and 24/7 operations are reportedly becoming untenable at many local stations.

A recent New York Times op-ed penned by Lowry, titled “A Hurricane Season Like No Other,” paints a picture of the agency as a husk of its former, pre-DOGE termination of some 800 roles.

“NOAA put out a mayday on May 13 asking remaining staff members to temporarily vacate their posts to salvage what was left of the nation’s critical warning network,” Lowry writes. “Nearly half of local forecast offices are critically understaffed, with a vacancy rate of 20 percent or higher, and several are going dark for part of the day, increasing the risk of weather going undetected and people going unprotected and unwarned,” he adds, citing staff reshuffling as a symptom of the agency’s of existential throes.

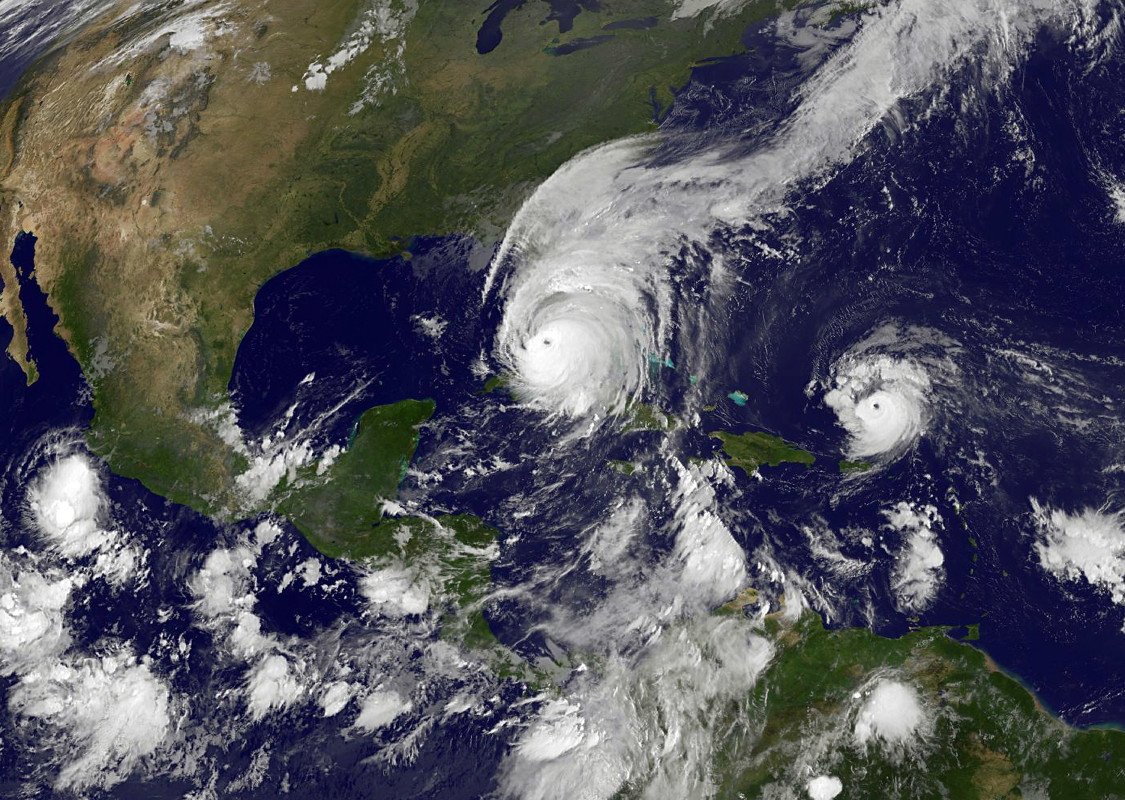

NOAA-NASA GOES Project via Getty Images

While this all might be, like, a total bummer for our up-to-the-minute surf forecasts this season, it could also be downright deadly for those of us living seaside and in hurricanes’ paths.

Weather balloons, which, even with the advent of satellites have remained a primary source of hurricane data collection for more than 60 years, are running at reduced rates. Typically launched twice daily from 100 North American, Caribbean, and Pacific sites, “weather balloons have been shown to markedly improve forecast accuracy, so much so that twice-daily launches are commonly supplemented with up to four launches a day ahead of major hurricane threats,” according to Lowry. They also critically inform “time-sensitive decisions like evacuation orders.”

Meanwhile, nationwide, balloon launches are down between 15 and 20 percent nationwide as we face what will likely be an especially active hurricane season. In some places, skeleton-crew staff at the National Weather Service are so preoccupied with other priorities that weather-balloon flights are suspended altogether. During hurricane season.

Related: NOAA Just Fired Hundreds Of Staff … Your Surf Forecast Is Going To Get A Lot Worse

While private equity toys with the idea of turning public services like weather forecasting into cash cows, it’s reported that the National Weather Service—which our tax dollars are still supposedly funding—costs the average American $4 per year. What’s your peace of mind worth? Hell, at base level: What’s a half-decent, subscription-free surf report worth?

When there is no hint of a blueprint, no modicum of a foundation for an alternative weather-forecasting system, administration, and/or agency, is hastily scrapping the one that’s in place—and which our very livelihood and lives, let alone recreation depend upon—in anyone’s best interest?

Could the private sector drum up a service to supplement or perhaps even supplant NOAA and the National Weather Service while doing it better and cheaper, as Project 2025 and its proponents propose? In a perfect world, why not? But then, “If the private sector could have done it better and cheaper, it would have,” summates Lowry, and the fact of the matter remains: “it hasn’t.”

How long do we want to wait? And how long could we have to wait for a reimagined weather service? The first one only took 155 years. Don’t hold your breath, though it might not hurt to keep an eye on the sky.